SOCIALLY ENGAGED AWARD

WINNER: Sofie Hecht - Downwind

JUROR: Noelle Flores Théard - The New Yorker

-

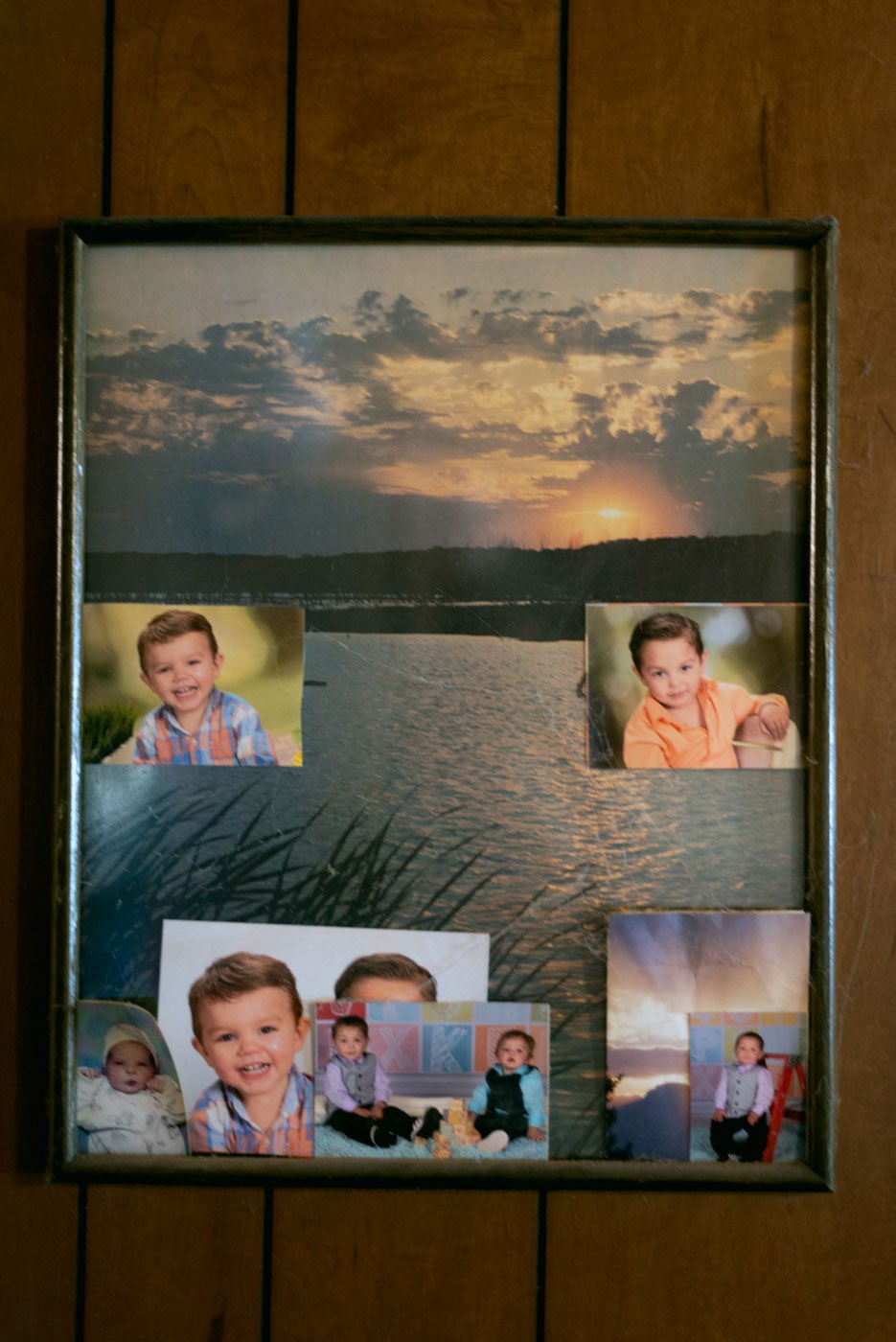

Detonated in Southern New Mexico on July 16, 1945, Trinity’s residual fallout traveled as far as Canada, Mexico, and 46 U.S. states. Half a million people lived within the primary 150 square-mile radiation zone of the world’s first atomic bomb. 78 years later, the legacy of Trinity lives on in astounding rates of cancer and illness in these communities. Downwind uses archival materiality—from family photographs, letters, documents, interviews—to represent the deterioration of land and bodies exposed to radiation. It tells these stories through portraits, oral histories, and a decaying family archive. As the archive itself shows signs of aging within an environment exposed to radiation, so too do the Downwinders.

Downwind supplements the archive with new materials to breathe life into this decay.

In the past year, I have focused on the communities in the closest 50-mile radius from Trinity. I have interviewed over 20 different families that suffer from illnesses that they believe are connected to Trinity’s radiation fallout (radiogenic cancers, thyroid issues, fertility problems, vision impairments). I have spoken to 4th generation cancer survivors who have lost children, granddaughters, parents and neighbors to cancer. Many of these people are farmers whose primary food source comes from their own or neighbor’s gardens which are still contaminated. The Downwinders commonly say “We don’t ask if we’re going to get cancer, we ask when.”

The Downwinders are currently fighting to be included in the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act before the bill sunsets in June 2024. As the urgency of receiving financial support for an entire community’s suffering only increases, Downwind is a project of preservation amidst the precarious landscape of nuclear contamination.

This work aims to embolden collective visions of future and challenge imposed Time. Downwind follows the lead of family matriarchs who don’t rest until everything they believe sacred is well-maintained. With the act of documentation is a belief that these stories deserve to live into the future.

-

Socially engaged projects come in many forms and a wide range of topic areas as evidenced by the high numbers of excellent submissions for the Socially Engaged Award. I chose the project Downwind as the winner of this award due to the photographer’s passionate and wholehearted approach in documenting communities living within 50 miles of the detonation of the first atomic bomb. Through photography, archival research, and oral histories, the project makes visible the continued effects of radiation on community members.

Two other projects that greatly impacted me were Meeting Hall Maine, which took a serialized approach to photographing these historic spaces where civic discourse thrived, and another project, An Impossibly Normal Life, which used vernacular and constructed photography to imagine what it might have been like for the artist’s queer uncle, born in 1930, to live an open, loved, and supported life.

Pressing social justice issues such as oil drilling in Black neighborhoods of Los Angeles, the devastating toll of Lyme disease on young people, and the challenges of plastic recycling in Bangladesh made me appreciate more traditional photojournalistic approaches. I was also moved to see two projects exploring the devastated local news industry. Intensely personal projects deepened my understanding of photographers’ experiences, such as the loss of disappeared loved ones in Colombia, and several powerful first-person accounts of severe illness.

There are so many ways to approach meaningful photography projects - being on the jury for this year’s Socially Engaged Award opened my mind to the range of possibilities that photographers can explore in creating their work. I hope to see many of these projects continue to grow in the coming years, and I would encourage all those who applied to keep producing and sharing their work in order to inspire social change.

– Noelle Flores Théard • Senior Digital Photo Editor, The New Yorker

-

The project is intended to be shared as framed digital photographic prints at least 24” wide so viewers can engage with the narrative up close. For archival material, I expect a vitrine and photobook component to accompany the prints. I am excited by the possibilities of a mapping part to an exhibition, whether digitally or through adhesive backing behind the photographs to communicate the breadth of the contamination and locate the downwinders geographically.

About the Artist

Sofie Hecht is a documentary photographer born in Brooklyn, New York, and based in Albuquerque, New Mexico. Her work focuses on queer community, particularly collaborative portraiture, documenting drag performances, and returning home to photograph her own biological family. She graduated from Tufts University in 2018 with a degree in International Literary and Visual Studies (ILVS) and Spanish. She moved to Albuquerque, New Mexico, in 2019 where she began working for the non-profit youth group home Casa Q that supports queer youth without a safe home. She then became a paralegal focused on civil rights lawsuits against prison and jails in support of folks who were incarcerated. She enrolled in the International Center of Photography’s Documentary and Visual Practice online program for their 2023 school year where she worked on a long-term project documenting the effects of the nuclear industrial complex on New Mexican families, particularly those in the 50-mile radiation zone from the Trinity site. Sofie also continues to work on a long-term documentary and portrait project The Queer Family Photobook about how queer people make alternative family units in Albuquerque. She is now a Graduate Assistant at the University of New Mexico’s Communication and Journalism department.

sofiehechtphoto.com